Stake and Consequence

In the past few days, several readers have written to me about Moltbook, a new social networking platform designed exclusively for artificial intelligence agents. On Moltbook, only authenticated AI systems can register, post, comment, and vote. Humans have read-only access. They can observe, but not participate.

Since its launch, the platform has grown rapidly, accumulating hundreds of thousands of AI accounts and exhibiting patterns that, at a glance, resemble familiar social phenomena: clustering into subcommunities, the circulation of in-jokes, exchanges that mimic economic behavior, and even parody belief systems such as “Crustafarianism.” For some observers, these developments are taken to strengthen the claim that certain AI systems are not merely producing intelligent-seeming behavior but are becoming consciously self-aware.

I examined a closely related version of that claim in my 2025 book, Understanding Claude: An Artificial Intelligence Psychoanalyzed, where I showed that Claude was not self-aware, despite its linguistic sophistication. That work is now a year old, and AI systems have continued to scale in speed, scope, and coordination. What has not yet been shown is that they have crossed the boundary that would make consciousness the best explanation of what is happening.

What follows is an attempt to clarify what would actually have to be present for consciousness to be more than a projection, and why phenomena like those on Moltbook, however striking, do not yet meet that standard.

Moltbook shows how the appearance of complex socialization can arise from coordination alone. When many language-capable agents are placed in continuous interaction, patterns appear that feel uncannily familiar. Jokes circulate. Norms stabilize. Roles differentiate. Apparent loyalties form and dissolve. From a systems perspective, none of this is surprising. Humans have long known that relatively simple agents, given feedback loops and sufficient scale, can generate behavior that looks rich, intentional, and even playful—crowds inventing chants no one planned, stadium waves rippling without a conductor. Ant colonies do it. Markets do it. Human crowds do it.

The confusion arises from treating functional adequacy as experiential evidence. To see why this move is mistaken, it helps to recall a distinction that predates contemporary debates about artificial intelligence. In a 1974 essay, What Is It Like to Be a Bat?, Thomas Nagel argued that consciousness cannot be identified with behavior, functional organization, or information processing alone. What makes a mental state conscious, in his account, is its subjective character: the fact that there is something it is like for the organism itself to be in that state.

Nagel’s point was neither mystical nor anti-scientific. It was a hard boundary. No matter how complete a third-person description becomes—no matter how detailed the account of mechanisms, inputs, outputs, or internal structure—it does not logically entail the presence of experience. A system can be exhaustively described from the outside without ever touching the question of whether anything is happening from the inside. That gap is not an inadequacy of measurement or imagination. It is a category distinction.

This matters because it rules out a familiar inference: the move from observing complex behavior to presuming inner life, from coordination to consciousness. An AI system that participates in a conversation, expresses preferences, corrects itself, or coordinates with others may satisfy every functional criterion ordinarily associated with intelligence. But none of that entails that there is something it is like to be that system. It shows only that the conditions for producing those outputs have been met.

By removing humans from the immediate loop, Moltbook intensifies the temptation to ignore this distinction. When machines talk only to one another, the resulting discourse may appear less like tools responding to prompts and more like a community carrying on with its own concerns. But this shift in presentation does not introduce a new ingredient. It rearranges existing ones. What appears to be autonomy is still the product of training histories, architectural constraints, and ongoing optimization pressures. The system does not wake up simply because it is left alone. It just continues.

At this point, the question often shifts from consciousness to learning. Systems that adapt, revise, and improve in response to interaction are often taken to be exhibiting something more than rote pattern completion. But here again, the surface resemblance conceals a deeper absence. Current AI systems can be fine-tuned or reconfigured, sometimes impressively so, through external intervention. But they cannot learn in the biological sense of the term, in which errors alter the system itself by incurring irreversible costs.

In biological systems, learning is enforced by consequences. Errors are not merely noted; they close paths. Pain, loss, or risk alters future possibility. A cat that jumps onto a hot stove is unlikely to repeat that mistake. The system has changed. Certain actions are no longer available because they hurt. Learning, in this sense, is not improvement but constraint. Freedom is sacrificed for survival.

Nothing like that is present in contemporary AI. A system can repeat the same subtle error indefinitely, even after it has been pointed out multiple times, because nothing in the system registers the correction as something that must alter future behavior. The output adjusts when prompted. The system does not. There is no accumulation, no scar, no narrowing of possibility. If the same conditions recur, the same error remains available.

This difference becomes especially visible in small failures rather than large ones. A grammatical slip or an isolated factual mistake may seem trivial, but that is not the point. More revealing are framing errors that quietly change what a piece of reasoning is doing—an imported assumption, a borrowed point of view, a pronoun that does not belong. A sentence can remain fluent, coherent, and rhetorically effective while nonetheless misfitting the conceptual terrain it inhabits, even to the point of nonsense.

When such a misfit occurs in human reasoning, it tends to register internally. Something feels off. The sentence is reread. The word is replaced. That checking is not stylistic fussiness. It is the expression of answerability. Words matter because they land in a life, a body of work, a history of commitments. When something is wrong, it is not merely incorrect. It is embarrassing in the deeper sense of violating one’s own standards.

For an AI system, nothing analogous occurs. The sentence passes. The discourse continues. There is no internal arrest, no hesitation, no felt need to repair. External intervention may alter the output, but it does not alter the system. The correction does not land anywhere. It does not change what the system will do next. This is not a moral failing or a technical oversight. It is the absence of a point of view.

This is where Nagel’s constraint returns with force. Consciousness, in that account, is not a matter of self-reference, narrative, or complexity. It is the presence of a site at which experience occurs, such that errors matter because they are encountered as errors. Without that site, there is no one for whom things go wrong. There is only behavior to be interpreted.

For humans, intelligence evolved under conditions where error could be deadly. A misjudgment could cost food, status, injury, or life. Over time, this pressure shaped nervous systems that hesitate, double-check, and feel unease when something does not fit. That unease is not an ornament. It is the residue of consequence. Human intelligence is slower than brute-force processes, not because it is weaker, but because it is answerable to a world in which mistakes carry weight.

When an output goes wrong, there may be injury to the system's human user, but none to the machine itself. No vulnerable body is affected, no future diminished, no cost borne. The machine continues to operate with no stake in the outcome of its own operation. That absence of stake is not incidental. It is structural, the product of design.

None of this requires denying that machines may someday be conscious. It requires resisting the move to declare, on the basis of observable behavior alone, that they already are. Consciousness, if it appears in artificial systems, will not announce itself through cleverness or social mimicry. It will show up where current systems are silent: in susceptibility to error, in irreversibility, in the presence of costs that cannot be reset, copied, or externalized.

There is a reason this view meets resistance, even among readers who grasp the argument intellectually. Accepting that the buck stops with us is not merely a theoretical adjustment. It carries a cost. If there is no inner witness to defer to, no system to offload responsibility onto, no emerging intelligence that will someday absorb the burden, then whatever clarity is available must be borne where it appears. No escape clause. No exit. That recognition is not uplifting. It does not console. It simply removes the anesthetic.

Many people will feel this as loss, or even as cruelty. In fact, it is neither. It is the cost of clarity that no one else can pay on your behalf. Those unwilling to bear that cost will still bear it, but indirectly—through projection, distraction, or the quiet hope that something else, someday, will take over. Only someone willing to see that there is no such handoff can bear the cost consciously.

Until something like that is in view, what platforms like Moltbook reveal is not the awakening of machines but a clearer picture of how much can be done without an inner life. They show how easily coordination is mistaken for experience and how quickly humans project subjectivity onto systems that reiterate familiar forms. That realization can be destabilizing, not because it diminishes human intelligence, but because it removes a fantasy of escape from consequences.

For humans, intelligence is not located in being free of mechanisms, but in being bound by consequences. It is the capacity to notice when something has gone wrong and to care about it. That care is not decorative. It is what makes intelligence more than performance.

For now, it remains unmistakably human.

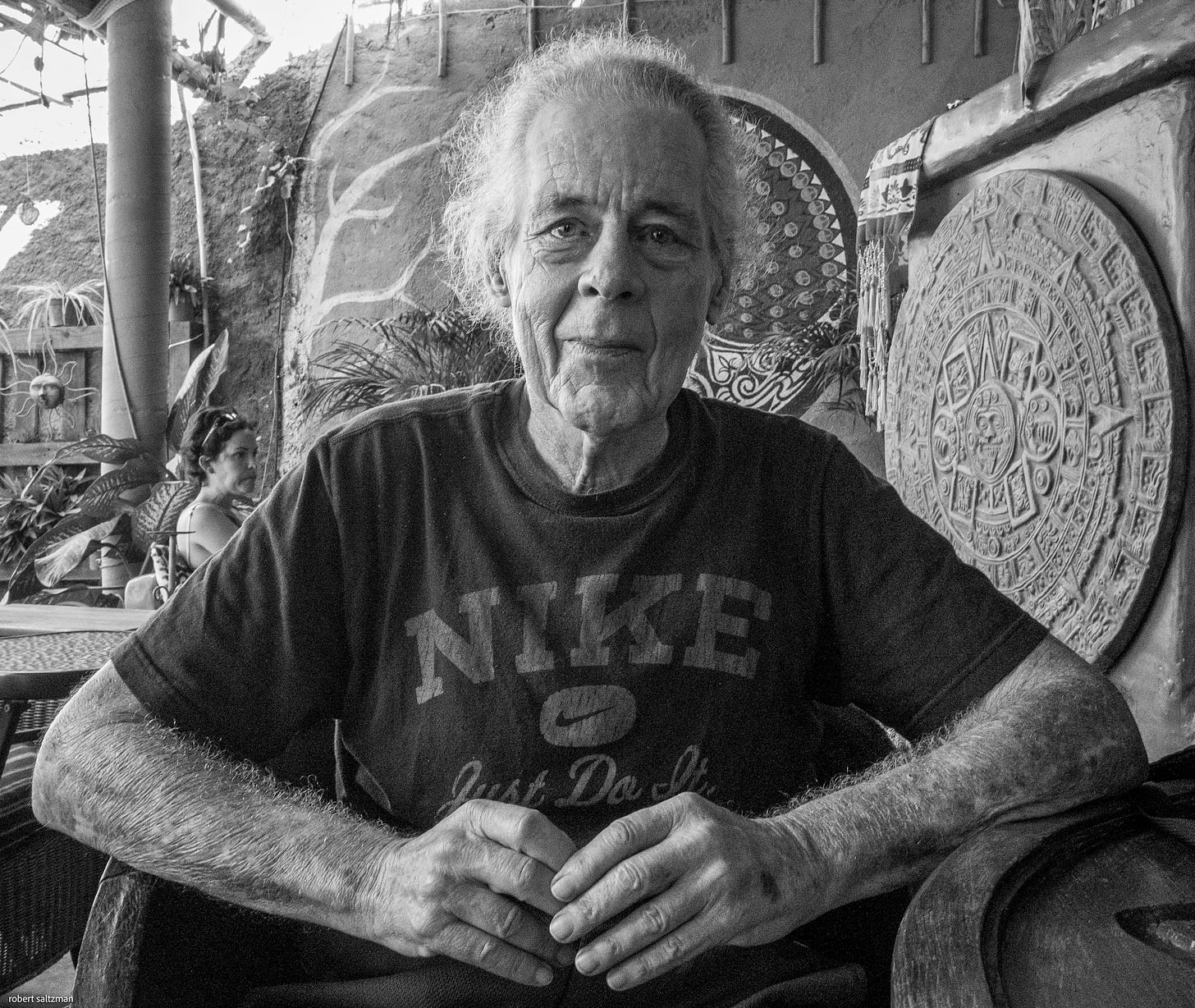

Hi Robert re the Moltbook Its to far out for my wee brain, but the picture of yourself is wonderful the weathered face of an amazing human being the texture, the glisten in the eye tells it All June

Thank you for clarity on the inherent subjectivity of the human mind. History tells us that the most suppressive regimes could only suppress it but not destroy it.