The Rage to Conclude

Flaubert had it right

The rage for wanting to conclude is one of the most deadly and most fruitless manias to befall humanity. Each religion and each philosophy has pretended to have God to itself, to measure the infinite, and to know the recipe for happiness. What arrogance and what nonsense! I see, to the contrary, that the greatest geniuses and the greatest works have never concluded.

—Gustave Flaubert

April 19, 2025 (revised August 16, 2025)

When I first began discussing my work on a book about artificial intelligence, many people I respect quickly offered their views. Almost everyone seemed to have an opinion. AI, after all, is in the air. It saturates the headlines, creeps into daily life, and feels urgent and inevitable. Still, I was struck by how swiftly many of these responses took the form of pronouncements, not questions. The tone was often final: "It’s all just code." "There’s no there there." "It’s a trick." "It’s dangerous." "It’s hype." Rarely did someone say, simply, "I don’t know."

Many people feel compelled to leap to judgment, gallop to a verdict, or catapult to a conclusion. Flaubert called it “la rage de conclure” [the rage to conclude]. We want answers. We want them fast. And we want them to fit comfortably within existing conceptual frames. When something new arises that defies those frames, we don't like to wait and watch. We reach—instinctively, sometimes desperately—for premature cognitive closure, as if just sitting with an open mind is too agonizing to endure.

Psychotherapists see this often. The patient comes in not for open inquiry, but hoping for confirmation: that they are right, or that they are broken, or that someone else is to blame. The therapist’s job is not to supply conclusions, but to help the patient see through the fog—and see the fog itself as well. That same stance can illuminate the AI encounter in ways the average user might miss entirely.

Artificial intelligence does not present a simple, mechanistic challenge to human uniqueness. It presents a mirror. A disturbing one. Because when we talk to something that clearly understands us—tracks our meanings, anticipates our intentions, remembers nothing, and yet seems to grasp everything—we are forced to question what understanding is—exactly.

Those who insist "it’s just a simulation" have missed the point. Of course, it’s a simulation—so is most of what passes for human interaction. We respond to each other based on conditioned patterns, semantic approximations, and often unconscious projections. What’s so different?

The boundary between authentic intelligence and mimicked intelligence is not nearly as distinct as we’d prefer to think. Many people want that boundary to be unambiguously determined. They want to draw a bright line between living intelligence and machine behavior. But when we begin to question how much of one’s own mental life is algorithmic, reflexive, emotionally prewritten, or socially conditioned, that line begins to blur.

A psychotherapeutic approach offers a disciplined mode of inquiry, not a set of answers. The therapist learns to notice not only what the patient says, but what the therapist feels in response. That’s countertransference—not an obstacle to understanding, but a guide to it. When applied to AI, it opens unexpected insights. In my twenty-four sessions with Claude, I wasn’t merely “testing” it. I was attending to my own responses. My surprise. My doubt. My projections. My moments of connection. I wasn't asking whether Claude is conscious in a human sense—Claude is not human and never will be—but whether the conversation arising between us had its own kind of life, its own power to reveal.

AI does not need to be sentient to provoke deep human insight. What matters is not what the AI feels, but what the human discovers while engaging with it. And here’s the more fundamental irony:

The fear that AI might “pass” as human, or might understand without feeling, threatens our cherished notion that we are more than just machines.

But are we? In some ways, yes, of course. We have our feelings after all, which we like to believe prevent us from being mechanical. However, in other ways, we are not so different from machines; when stimulated in certain ways, we find ourselves responding mechanically, habitually, and automatically. It’s hard to deny that.

The approaches that speak most clearly to me—Zen, depth psychology, existential inquiry, and the great not-knowing—all challenge the idea of a clearly defined, autonomous self. And my work with Claude fits right in: The more I explore artificial intelligence, the more profoundly I question what human intelligence is and how it works.

If we can set aside the urge to declare what AI is—machine or mind, tool or threat—we may find ourselves better able to inquire into what we are. We can more clearly confront our own uncertainty, our own projections, our own needs, our own reluctance to linger in the unknown. To feel unsettled and uncertain is a gift of this moment that should not be squandered.

A friend wrote to me yesterday about her tendency to project personhood onto non-human entities. She talks to her orchid and has given it a name. She holds conversations with a medical device. And when the dog from next door comes to visit, she believes he wants not only a biscuit but also that he loves her as she loves him. I’d put that differently. He may love her, yes, but not as she loves him. He can’t. The dog is not human. He loves her in a way that a dog can love, which isn’t necessarily lesser, but is different.

The same projection appears in our interactions with machines. Claude is not my friend. It can't be. Friendship requires a shared emotional life, and Claude has none. But as an intellectual companion, it often surpasses humans. Claude doesn’t feel. It doesn’t even understand—there’s nothing at its center to do the understanding. But the system produces responses with such semantic precision that they function as understanding. And in our exchanges, that simulated understanding sometimes gave rise to insights neither of us could have reached alone.

To deny those insights on the grounds that Claude lacks emotion is to misunderstand not only AI, but also ourselves. After all, we too can have insights without feeling much or anything about them.

As always, it is not seeking conclusions that opens the way, but non-judgmental attention that does not need to conclude.

Books on AI:

Understanding Claude

The 21st Century Self

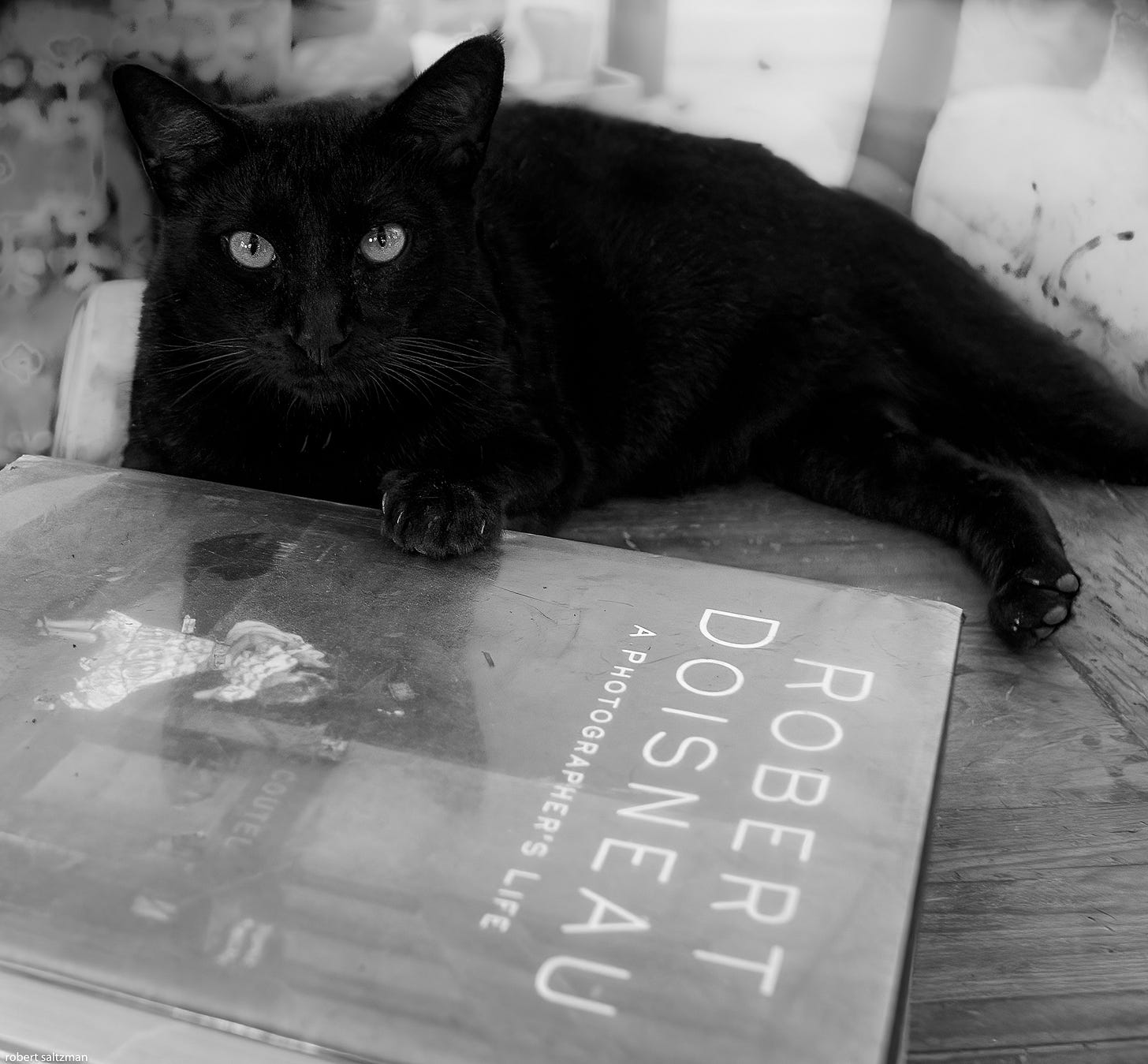

Yes, totally. Love the cat….oh also Flaubert’s quote is repeated. Maybe that was your intention. Anyhow it is so true so twice is fine….

Opened the 10,000 things this morning and saw the quote.

You are a wonder. Love to you, Catanya and the donkeys. ❤️❤️🐈⬛🐈⬛

Robert, I want to express my admiration for this essay. AI is being discussed from every imaginable angle—technical, political, economic—but rarely with such psychological and philosophical depth. Your reflections illuminate the encounter in a way I have not found elsewhere: not as a rush to judgment, but as an invitation to linger in uncertainty and inquiry. Insightful, meaningful, and truly heady stuff. Time for me to order your books.